Decades before Adam Lanza shot 26 kids and teachers at a school in Newtown, Conn., before James Holmes killed 12 people and injured 70 more at movie theater in Aurora, Colo., and before Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold killed 12 students and a teacher at a high school in Columbine, Colo., there was Charles Whitman.

As David Eagleman describes it in an Atlantic article from 2011:

On the steamy first day of August 1966, Charles Whitman took an elevator to the top floor of the University of Texas Tower in Austin. The 25-year-old climbed the stairs to the observation deck, lugging with him a footlocker full of guns and ammunition. At the top, he killed a receptionist with the butt of his rifle. Two families of tourists came up the stairwell; he shot at them at point-blank range. Then he began to fire indiscriminately from the deck at people below. The first woman he shot was pregnant. As her boyfriend knelt to help her, Whitman shot him as well. He shot pedestrians in the street and an ambulance driver who came to rescue them.

Whitman killed 13 people from the tower and wounded 32 more. He had been an Eagle Scout and a marine, and was apparently very happily married before he also killed his wife (like Lanza, he also killed his mother before taking his rage public). He had an IQ of 138 and studied architectural engineering. But something had changed for no apparent reason.

“I don’t really understand myself these days,” he wrote in a revealing suicide note the night before.

I am supposed to be an average reasonable and intelligent young man. However, lately (I can’t recall when it started) I have been a victim of many unusual and irrational thoughts. These thoughts constantly recur, and it requires a tremendous mental effort to concentrate on useful and progressive tasks.

Before the end of the letter he asked that doctors perform an autopsy and examine his brain so that society could learn what had gone wrong. As it turned out, he had developed a small brain tumor that, as Eagleman describes it, “had blossomed from beneath a structure called the thalamus, impinged on the hypothalamus, and compressed a third region called the amygdala.”

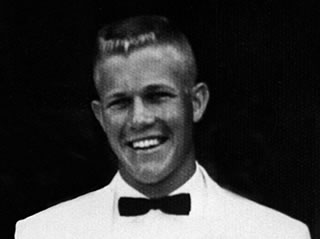

Whitman on his wedding day. A few years later he would kill his wife and a whole lot of other people. Image via Murderpedia

Brain deformity as a cause of violence has been extensively explored because of cases like Whitman’s. Last week, news emerged from Lanza’s autopsy, disappointing those who had hoped it would reveal some kind of obvious brain deformity. It did not.

But the reverse relationship has been less explored: the effects of violence on the brain. While it's known that violent people tend to have a history of psychological trauma during childhood, new science has identified a link, suggesting that brains change not just psychologically but physiologically when exposed to trauma early on.

“In a challenging social situation, the orbitofrontal cortex of a healthy individual is activated in order to inhibit aggressive impulses and to maintain normal interactions,” said the study’s leader, Carmen Sandi, head of the Laboratory of Behavioral Genetics at Switzerland's EPFL. The orbitofrontal cortex is the part of the brain that controls decision making.

“But in the rats we studied, we noticed that there was very little activation of the orbitofrontal cortex,” she continued. “This, in turn, reduces their ability to moderate their negative impulses. This reduced activation is accompanied by the overactivation of the amygdala, a region of the brain that's involved in emotional reactions.”

Previous research has found the same low levels of orbitofrontal activation and the same corresponding inability to moderate aggressive impulses in the brains of violent humans. "It's remarkable; we didn't expect to find this level of similarity," Sandi said.

Sandi and her team also made another interesting finding that highlights the genetic influences on violence: that traumatic experiences for rats caused long-term changes in gene expression for genes associated with aggressive behavior, specifically the Monoamine oxidase A, gene, or MAOA, which is sometimes called, controversially, the "warrior gene." Using anti-depressants that inhibit that gene, researchers managed to effectively reverse the rats’ aggression.

Aggro rats. Image by Jay Odjick, via DeviantArt

In other words, just because childhood trauma may hardwire your aggression, as this study suggests, anti-depressants, may help effectively rewire you for the better. It’s an encouraging thought, considering the re-wiring done by violence seems to send its victims--be they children living in abusive homes or in war zones--down a destructive spiral, in which trauma causes brain changes, which, in turn, dispose them more toward violence.

The research also raises some sticky ethical questions with regard to our criminal justice, which favors punishment over therapy. Why, for example, is a physiological brain change any different because it's caused by social factors and not so-called natural causes, as we believe it was with Whitman? (It should be noted—albeit, very inconclusively—that despite his outward normalcy, Whitman suffered childhood traumas of his own at the hands of a what he called an abusive father.)

That said, where do we draw the line? As Eagleman notes in the Atlantic article, carriers of one particular set of genes are “three times as likely to commit robbery, five times as likely to commit aggravated assault, eight times as likely to be arrested for murder, and 13 times as likely to be arrested for a sexual offense." A full 98.1 percent of the inmates on death row carry that gene set. “If you’re a carrier,” he quips, “we call you a male.”

Lead image by Zoriah Afghanistan Children, via RAWA News